ENOLA GAY- The Men & the Mission which brought World War II to an end

Since first announcing the print “The Peacemakers” the reaction has been very complimentary. Many have responded positively with comments, not only with kind words about the artwork, but also expressing appreciation for the subject matter, which we realized would be controversial to some. In truth, ever since since August 1945, the Enola Gay, its mission and those who participated in it, have remained the subject of debate across the world.

So…why do a painting featuring the men and machines which can potentially stir up such debate?

Quite simply, as in all the paintings I create (and I think I speak for most of my fellow aviation artists as well), it’s never the intention to ‘glorify’ what war was or is, but rather keep the history alive so we will not repeat it. Highlighting the bravery of many who were willing to make the sacrifices necessary to preserve and protect the lives & freedom of those they loved from tyranny is the goal.

It’s my opinion that over the past few decades, so much of our history has become sadly misrepresented, whether in media or modern education systems, and the valor of those of that generation is in danger of being forgotten, or even worse, maligned. It’s been a privilege for me over these past few decades to know many of those great people, and if my artwork can help in some small way to keep the memory of what they did preserved for future generations, it’s an honor.

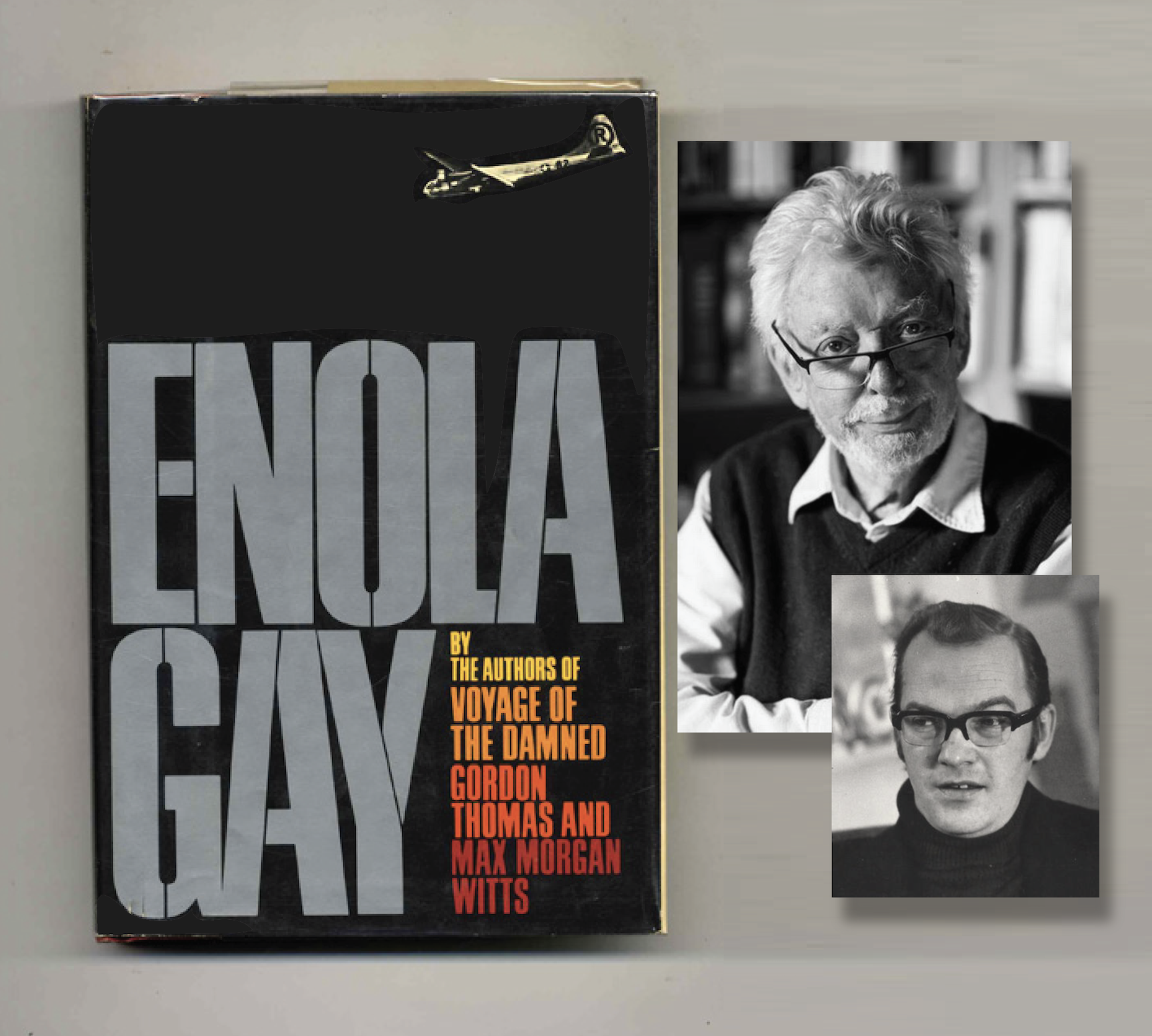

ENOLA GAY by Gordon Thomas & Max Morgan Witts.

Since I began creating paintings depicting aviation missions during the war years, few books have fueled my imagination so vividly as this book ENOLA GAY by authors/historians Gordon Thomas & Max Morgan Witts. Originally published in 1977, the authors tell the entire story of the times, the circumstances and the monumental effort it took on the parts of so very many people to bring the war to an end, from the Manhattan Project to those final days on Tinian. Especially fascinating to me were the efforts made to keep everything top secret, especially with so many involved in so many different capacities.

Dealing with this highly-controversial subject, the authors make no personal judgements about the ethics or morality of the decision to use the atomic bomb they just present the historic facts of what happened in a concise and riveting way.

The personalities & relationships of the people involved, such as Col Tibbets, Robert Oppenheimer, General Groves, individual members of the Enola Gay crew and other personnel of the 509th vividly come to life. Also fascinating are the well-researched perspectives of many Japanese involved, both before and following those terrible final days of World War II.

This book received well-deserved critical acclaim from people who lived through those times on BOTH sides… a few examples:“This is the way it was- warts and all . Reading this account took me right back to those momentous days when I helped change the face of warfare. I endorse this book unreservedly. It stands as the finest work written about all of us”. - Maj. ROBERT LEWIS, Copilot of the Enola Gay. “I found this book filled in the gaps in a way no other has done. I recommend it without hesitation.” - Maj. Gen. SEIZO ARISUE, Director of Intelligence, Japanese Imperial Army, 1945

This great book has been out of print for a while now, but is still quite easy to find, either on Amazon, Ebay or many used book stores. I HIGHLY recommend it as well!

August, 1945…The B-29 Superfortress named “Enola Gay”, the innocent-sounding name of a quiet lady back in the States, and the mother of the man would pilot the plane that would soon begin to change the course of history, sits poised and ready for the next day’s fateful mission.

Three months earlier, Germany had surrendered and the war in Europe had come to an end, but the terrible carnage in the Pacific continued. Despite increasing enormous daily losses, Japan showed no sign of surrender, and a land invasion was imminent. Every man, woman & child was preparing for this nightmare on their home soil, estimates of casualties were in the millions, and no one could foresee a date that the war would end…Since being informed that the U.S. had won the race of harnessing the atom as a weapon, President Truman faced a terrible choice whether or not to try bringing the war to an abrupt end.

Thousands of men and women across America had been working to achieve this, as part of the top-secret Manhattan Project, from the scientists & physicists at labs in California & Los Alamos, New Mexico to the myriad of workers at Oak Ridge, Tennessee’s nuclear development sites. Each person performed a vital specific task, a piece of a puzzle which none were aware would look like when complete. All of their round-the-clock toil would culminate into one final effort to bring the war to an abrupt end, and avoid the horrible implications of a prolonged land war on the Japanese mainland.

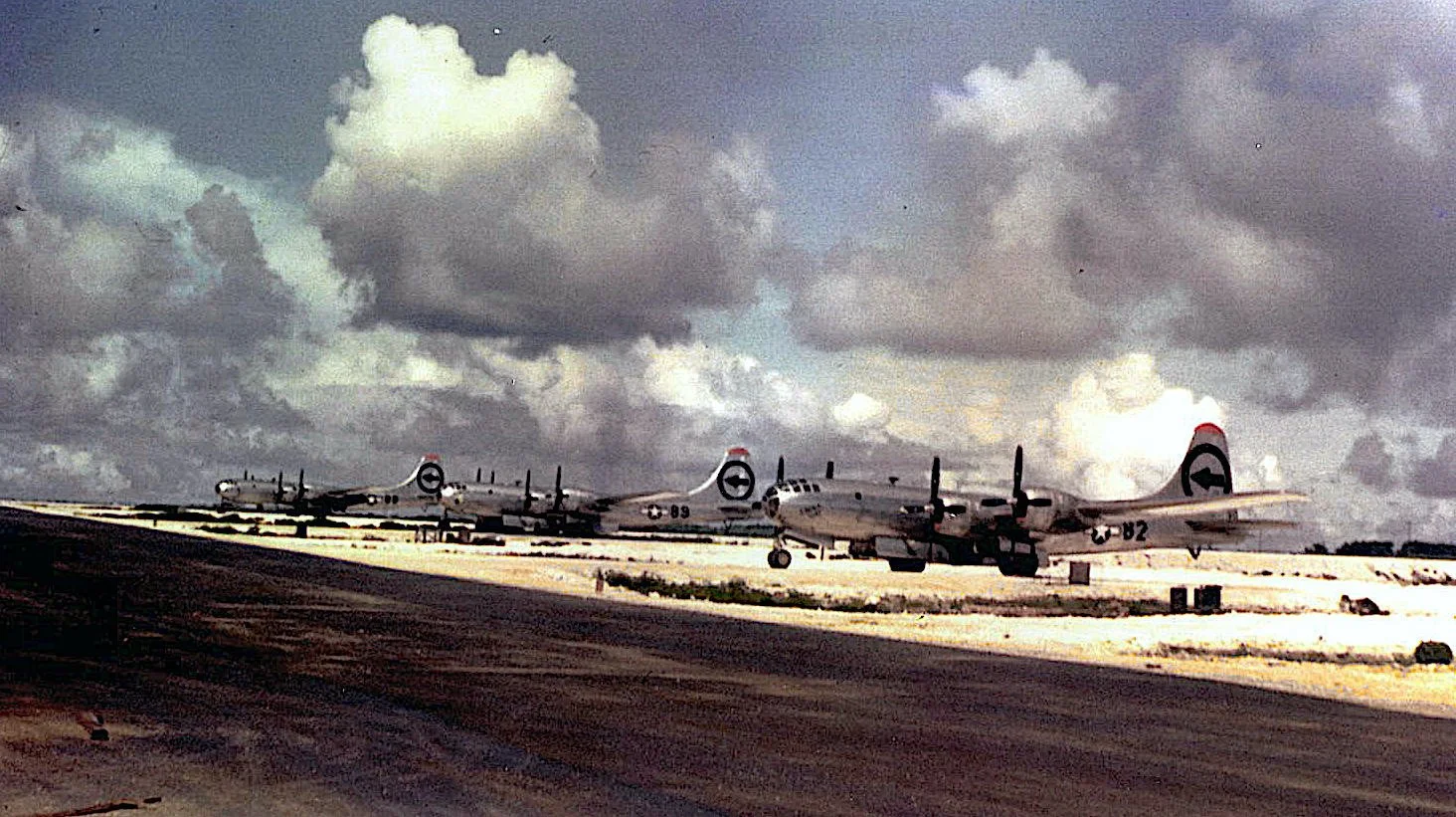

Tinian Island, August 1945, home of the 509th Composite Group. Approximately 1,500 miles from mainland Japan, after being seized by the Allies late July, Tinian became the main staging base for continuous heavy bomber attacks on the Japanese Islands. Shown here is a lineup of “Silverplate” B-29s, with Enola Gay in the foreground. Aircraft of the 509th bore the tail marking of a large circle & arrowhead. These markings would be repainted temporarily with emblems from other Pacific bomb groups in the vicinity just prior to the atomic missions, to confuse the ever-watchful enemy.

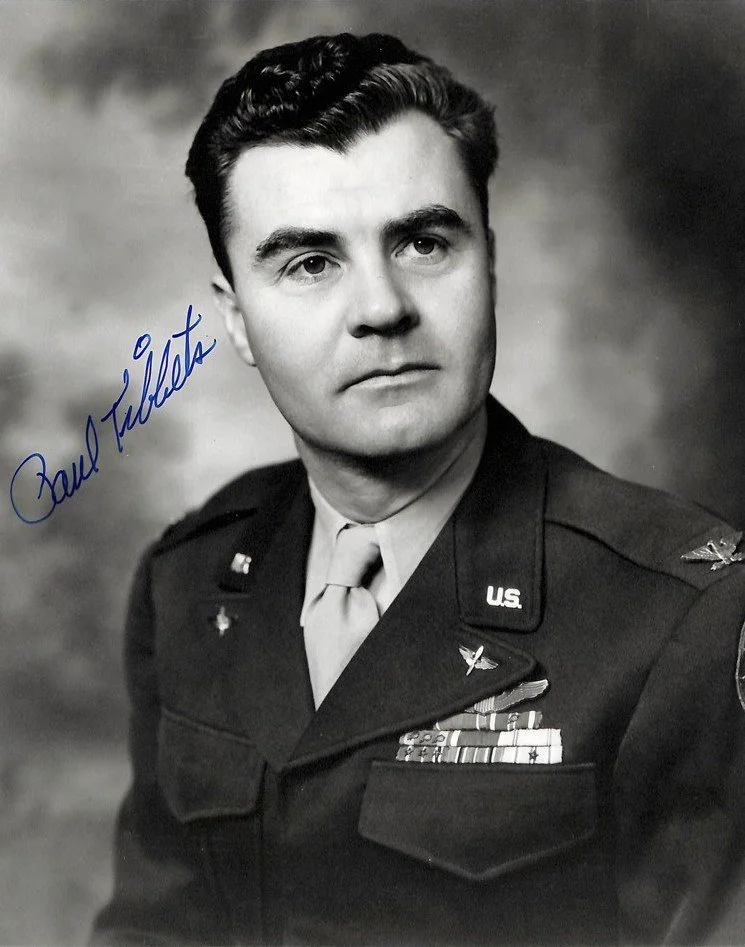

Paul Tibbets

Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress had been in development for some time by the latter part of the war, and in many respects was the most advanced aircraft of the time. Hap Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces, knew that to successfully implement the atomic strike against Japan, it would require the experience and knowledge of an extraordinary leader. Arnold consulted General James Doolittle, who, without hesitation, recommended Paul J. Tibbets for the job.

Not only was Tibbets a highly-experienced combat pilot of many B-17 missions from America’s earliest days of daylight bombing in Germany, but was also extremely familiar with the B-29, having been involved in its development, test-flying and simulated combat missions. Promoted to Colonel in January 1945, Tibbets was hand-picked to organize one of the most extensive top-secret military aviation units in history, the 509th.

To expedite specialized training of the air crews and support personnel, Tibbets was given carte blanche to choose the training location, personnel, and virtually ANY equipment he required to quickly assemble and accelerate the myriad of classified duties necessary to move toward the ultimate mission, with secrecy being the number one priority at all times.

To the dismay of many of the 509th, Tibbets chose the remote, god-forsaken desert air base at Wendover, Utah for the self-contained group’s initial training, to maintain the highest security. He’d implement extreme measures to ensure not a single person ever discussed even the slightest aspect of their individual jobs with anyone outside their immediate group, nearly none of whom knew exactly what their ultimate mission would be. By April / May of 1945, the group would be moved to Tinian to prepare for the final attacks on Japan.

Tibbets, had to remain relatively aloof from most of his personnel while carrying the burden of knowing the importance of secrecy of this mission. In light of this, he knew he needed a few men whom he trusted beyond their professional resumés- a few fast friends and fellow veterans with whom he could confide, and who he’d come to trust with his life. Two such men were Major Tom Ferebee and Captain Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk. Knowing he would be piloting the plane which would carry out the first atomic strike, Tibbets also hand-picked the crew he wanted to carry out the mission, but these two, his bombardier and navigator, would comprise his 'inner circle'.

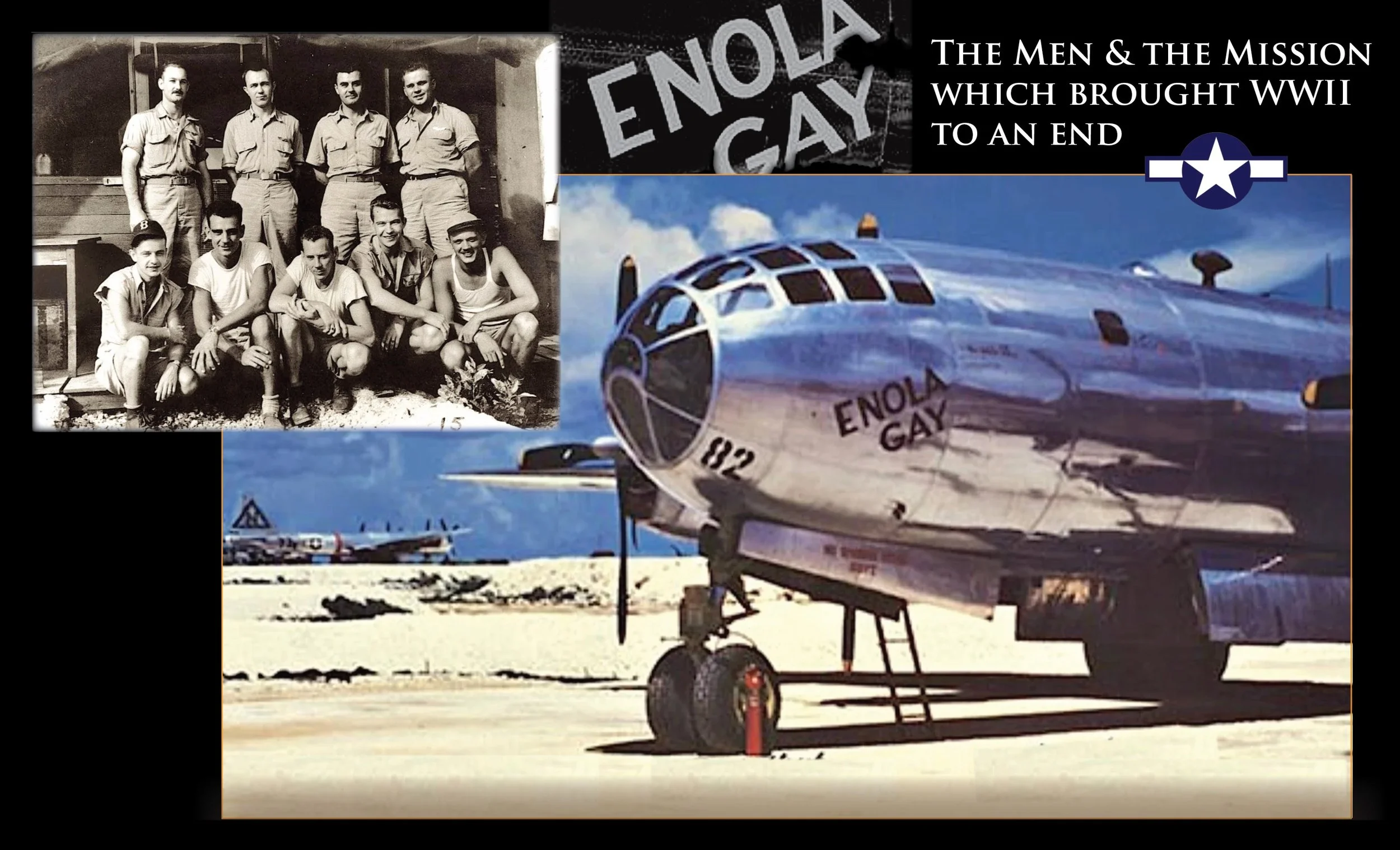

The “Red Gremlin”

Tibbets, Van Kirk and Ferebee’s work together began In August 1942. Paul Tibbets had flown the lead bomber in the 1st American daylight heavy bomber mission, a shallow-penetration raid against a marshaling yard in Occupied France. He would go on to fly more than 25 missions against the Germans, most of which were with Van Kirk and Ferebee in a B-17 named “The Red Gremlin”. In this photo, Tibbets & Van Kirk are the first two standing in the back row, & Ferebee is 4th in the row.

Crew of the Enola Gay

This famous photo, taken in the early morning hours of August 6, 1942, shows the air crew of Enola Gay, shortly before their historic mission.

Standing, back row: Lt. Col John Porter (ground maintenance officer), Capt. Theodore J. "Dutch" Van Kirk, navigator; Major Thomas W. Ferebee, bombardier; Col. Paul W. Tibbets, pilot; Capt. Robert A. Lewis, co-pilot; and Lt. Jacob Beser, radar countermeasure officer.

Left to right, front row: Sgt. Joseph S. Stiborik, radar operator; Staff Sgt George R. “Bob” Caron, tail gunner; Pfc. Richard H. Nelson, radio operator; Sgt. Robert H. Shumard, assistant engineer; and Staff Sgt. Wyatt E. Duzenbury, flight engineer. The other two individuals that participated in the flight, weaponeer and mission commander, Capt. William S. Parsons of the U.S. Navy, and his assistant, 2nd Lt. Morris R. Jeppson, are not pictured.

Enola Gay is backed over the bomb-loading pit on Tinian

With its usual arrowhead replaced by a deceptive “R” within the circle painted on its huge rudder, Enola Gay is backed over the bomb-loading pit on Tinian the day before the strike. The top of the first atomic bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy” is slightly visible, waiting to soon be carefully hoisted into the massive bay of the B-29. Note the tail markings of other planes in the background; The circle R designation (and the circle W on the B-29s in the background) were those of the 6th Bomb Group. These would soon be repainted back to their usual 509th motifs

Enola Gay safe return to Tinian, after the mission at 2:58 p.m.

Having lifted off just after 2:30 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the B-29 Enola Gay and its crew flew the first atomic mission in history. Having crossed the Japanese shoreline at 8:30 a.m. at a bombing altitude of 30,700 ft, they received a coded message from the weather plane Straight Flush. Cloud cover over Hiroshima was less than 3/10 at all altitudes, and they would strike the primary target as briefed. At 9:15 a.m. (8:15 local time in Hiroshima), the bomb was loosed, exploding at the preset altitude of 1,890 feet. Though the crew had repeatedly practiced the extreme evasive maneuver which would theoretically spare destruction to their aircraft from the resulting shock wave, no one aboard knew for sure what effect they would experience. Though violently rocked by the wave, they were able to safely return to Tinian, touching back down at 2:58 p.m.

RELIEF seen on the faces of Tibbets and Van Kirk after returning to Tinian.

A combination of exhaustion and relief is seen on the faces of Tibbets and Van Kirk in this rare color photo taken shortly after returning to Tinian. Moments later, General Carl Spaatz would pin a Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbets.

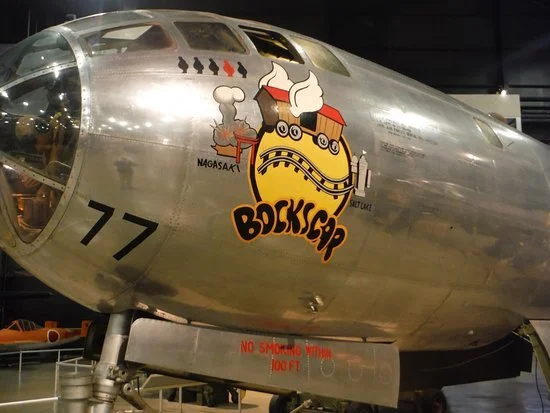

"BOCKSCAR"

Bockscar returned to the US in November 1945. In 1946, it was placed on display as the aircraft that bombed Nagasaki, but in the markings of The Great Artiste, at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona. It was flown to Ohio in September of 1961, where its original markings were restored. Bockscar is now on permanent display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, Ohio. This display, a primary exhibit in the museum's Air Power gallery, includes a replica of the “Fat Man” bomb and signage that states "The aircraft that ended WWII".

“Bockscar" was the name given to the B-29 which flew the 2nd and final atomic mission over the city of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, effectively bringing a decisive end to World War II. Named as a play on words for its usual assigned pilot, Frederick C. Bock, Col Tibbets chose Maj. Charles Sweeney, the 393d Bombardment Squadron's commander, to fly the mission, along with his crew of 'The Great Artiste', the B-29 originally scheduled to fly the 2nd nuclear mission.

The decision to change planes was made because their aircraft had been fitted with observation instruments for the Hiroshima mission. Moving the instrumentation from The Great Artiste to Bockscar would have been a complex and time-consuming process, and when the second mission was moved up from August 11 to the 9th due to adverse weather forecasts, the crews of both planes exchanged aircraft.

Kokura was the primary target, but due to a series of mishaps involving rendezvous times and weather over the target, they were unable to drop the bomb visually. After several passes, 1st Lt. Jacob Beser, reported Japanese activity on the Japanese fighter direction radio bands, and the decision was made to divert to the secondary target, Nagasaki. Still inhibited by cloud cover, after visually dropping the bomb (nicknamed “Fat Man”), detonation occurred approximately 1.5 miles northwest of the planned aiming point, resulting in the destruction of about 44% of the city.

Crew of “Bockscar”

Crew of “Bockscar” Master Sgt. John Kuharek (Flight Engineer), Staff Sgt. Albert Dehart (Tail Gunner), 2nd Lt Fred Olivi (Third pilot), Staff Sgt. Ed Buckly (Radar Operator), Capt. Kermit Beahan (Bombardier), Maj. Charles Sweeney (Pilot), Sgt. Raymond Gallagher (Asst. Flight Engineer), Capt. James Van Pelt (Navigator), 1st Lt. Charles Alsbury (Copilot), Sgt. Abe Spitzer (Radio Operator). Not pictured: Cmdr. Fred Ashworth (Weaponeer) and Lt. Jacob Beser (Electronic Countermeasures- Beser also flew aboard Enola Gay on August 6).

Charles Sweeney & Paul Tibbets

Charles Sweeney and Paul Tibbets, following Bockscar’s August 9th mission. John T. Correll, an historian and contributor to Air Force Magazine wrote: “The death toll from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where the second atomic bomb fell Aug. 9, was staggering, but these two missions finally brought an end to the war in the Pacific, where more than 17 million people had died at the hands of Imperial Japan. The war’s end also meant that the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands—an operation several times larger than the D-Day landings at Normandy, with expected casualties exceeding Hiroshima and Nagasaki put together—would not be necessary.”

On August 15, in a radio message known as the “Jewel Voice Broadcast”, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan to the Allies. The formal surrender took place aboard the USS Missouri, Sept. 2, 1945.

THE PEACEMAKERS by John Shaw

The famed B-29 Enola Gay undergoing final preparations the day preceding the first atomic mission, August 6, 1945.

In this scene, Col. Paul Tibbets two of his closest crewmembers, Capt. Dutch’ Van Kirk (navigator) and Maj. Tom Ferebee (bombardier) discuss final plans for the next morning’s historic mission. Its top-secret cargo already loaded, the massive B-29 sits in its hardstand, just having had the words “Enola Gay” (the name of Paul Tibbets’ mother) painted on its nose. As Military Police, other members of the flight and ground crews go about their duties, none are certain what the next few days will hold, yet all are aware that they will be playing a role in changing the course of history, hopefully resulting in peace, and the end of the most terrible war the world had yet seen.